Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertions: Better Outcomes Through Better Communication

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

–George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950)

Advancing American Kidney Health

While the Executive Order set forth bold goals to increase home dialysis utilization amongst patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD),1 the COVID-19 pandemic has served as an even greater impetus to allow appropriate patients to dialyze at home. In many areas, the cancellation of elective surgeries has led to delays in getting appropriate accesses created for our ESRD patients. For some, timely access creation was an issue even before the pandemic.

Thankfully, in a critical announcement, CMS made clear that peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter placements are not elective procedures and should proceed as scheduled.2 Despite this, getting a PD catheter placed at this time will likely involve a direct conversation between the nephrologist and the surgeon. In an era of texting and secure messaging apps, direct verbal communication between physicians has become an unfortunate rarity. I would like to offer some suggestions on how to improve communication with our surgeons who place PD catheters and ideas on how to monitor and improve procedural outcomes.

Building Surgical Experience

Efforts to grow peritoneal dialysis include PD catheter insertion by a competent operator. This is necessary to affect safe and timely initiation.3 Before considering how to improve communication with our surgical colleagues, we must consider the challenges they face in obtaining adequate experience in this procedure.

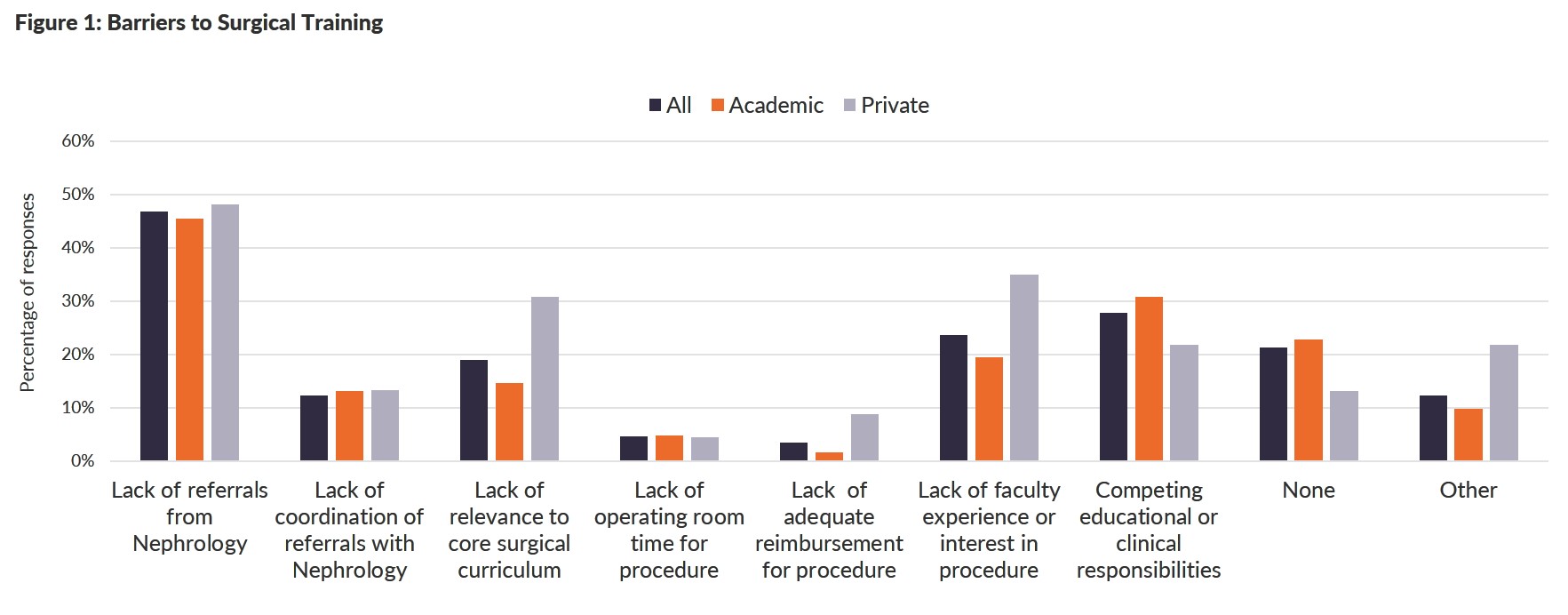

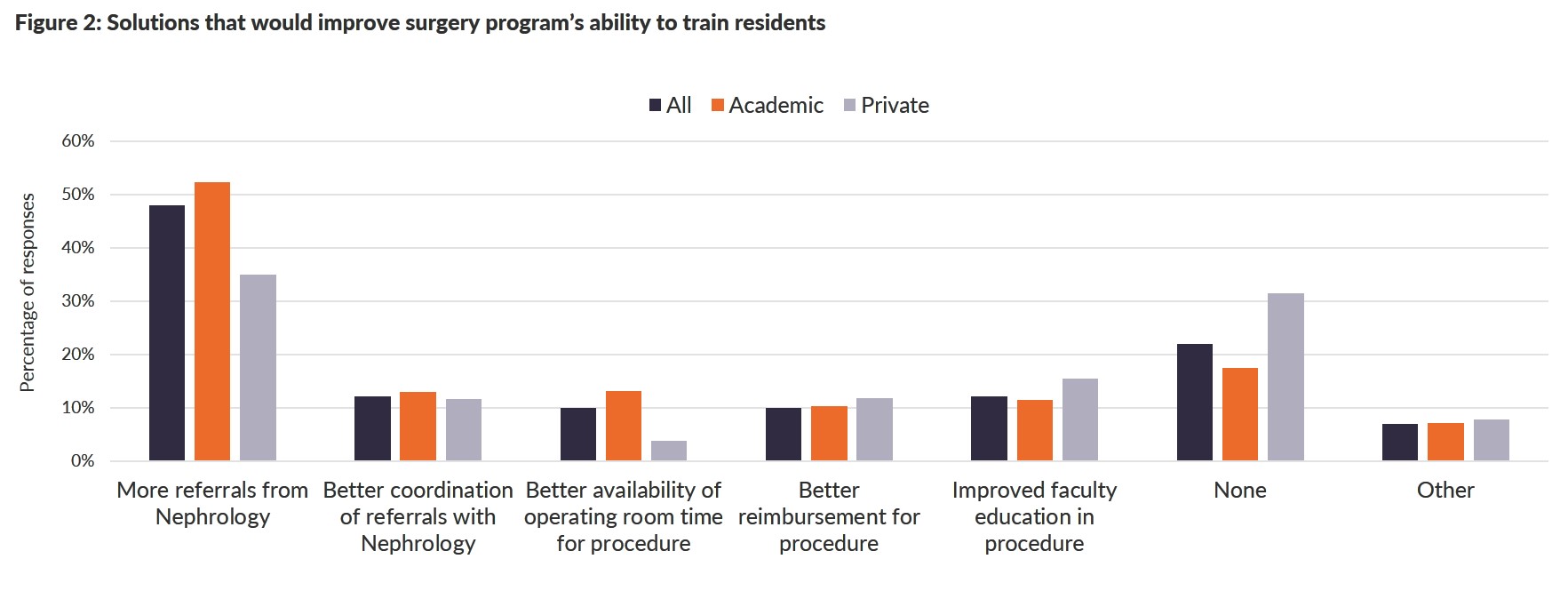

In a national survey of surgical residency program directors, Wong et al. noted that training appears to be inadequate.4 The large majority of operators were surgeons followed by interventional radiologists and lastly nephrologists. Astonishingly, 52% of responding program directors ranked priority in training surgical residents in PD catheter insertion as neutral to completely irrelevant.4 Yet, 62% of program directors felt that they could provide more training in surgical PD catheter placement if asked.4 The main barrier to surgical training was lack of referrals from nephrology. The main solution that would improve surgery programs’ ability to train residents was more referrals from nephrology.

Figures redrawn from source: Wong LP et al. Training of Surgeons in Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Placement in the United States: A National Survey.4

Suboptimal training can lead to PD catheter complications that result in a patient never starting PD or terminating it prematurely. A prospective multi-center study of laparoscopic PD catheter insertions found insertion-related complications resulting in significant adverse events occurred in approximately one in four patients within 6 months of insertion.5 The main cause of complications in patients in whom PD was never started or terminated early was flow restriction. In order to improve these outcomes, nephrologists need to better advocate for our patients by communicating with the surgical community.

Communicating the necessity for improvement

There is a plethora of medical literature regarding the importance of physician-to-patient communication and how to improve it. However, the opposite is true of physician-to-physician communication. There is little if any guidance on how to cultivate better relationships amongst physicians. I have used a multi-pronged approach, described below, to improve communication with my surgical colleagues to try to improve the timeliness of catheter insertion and outcomes of PD catheter placements. Of course, this communication should involve the entire team; including representatives from the nephrologist’s office, surgeon’s office and PD unit that focus on implementing a streamlined and safe process to initiate a patient on PD.

Step 1 – Collect data

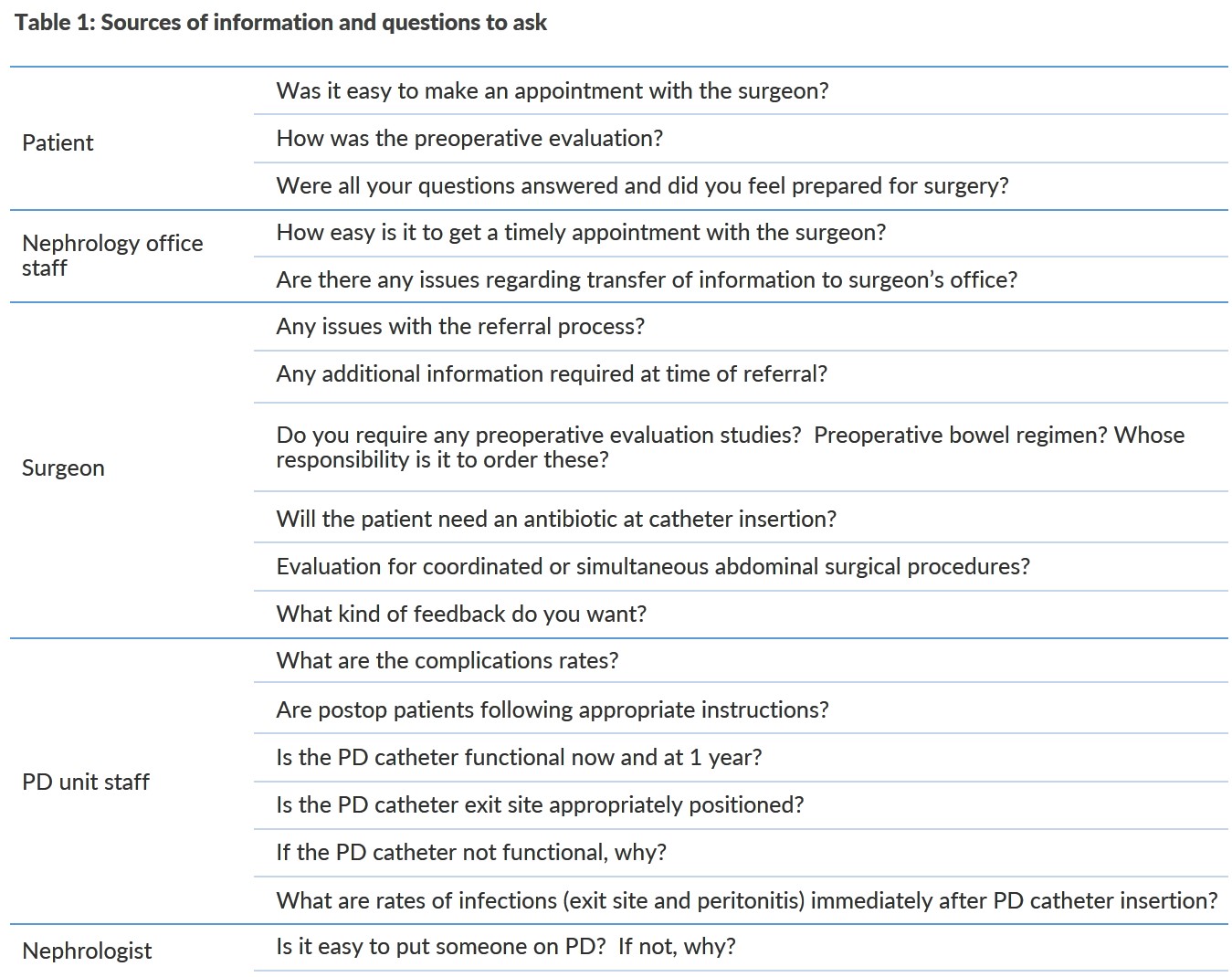

The first step is to collect your local data. There are multiple sources of information which can help the team improve every step in the process.

Your dialysis organization may already provide a tool for tracking this data which can be a great place to start. In 2015, the North American Chapter of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) established the North American PD Catheter Registry to improve practices and patient outcomes following PD catheter insertion.6 If neither of these meet your requirements, then you can create your own database to track the outcomes. I have used an spreadsheet to track our outcomes.

As with any metric development, it is very important to discuss which ones are meaningful to patient outcomes and to the physicians providing patient care/services. We chose to focus on:

- Number of catheters placed

- Number of catheters replaced

- Catheter function failures

- Catheters removed

- Complications; leakage outflow or inflow obstructions, constipation, manipulations, hernia, infection and omentopexy requirements

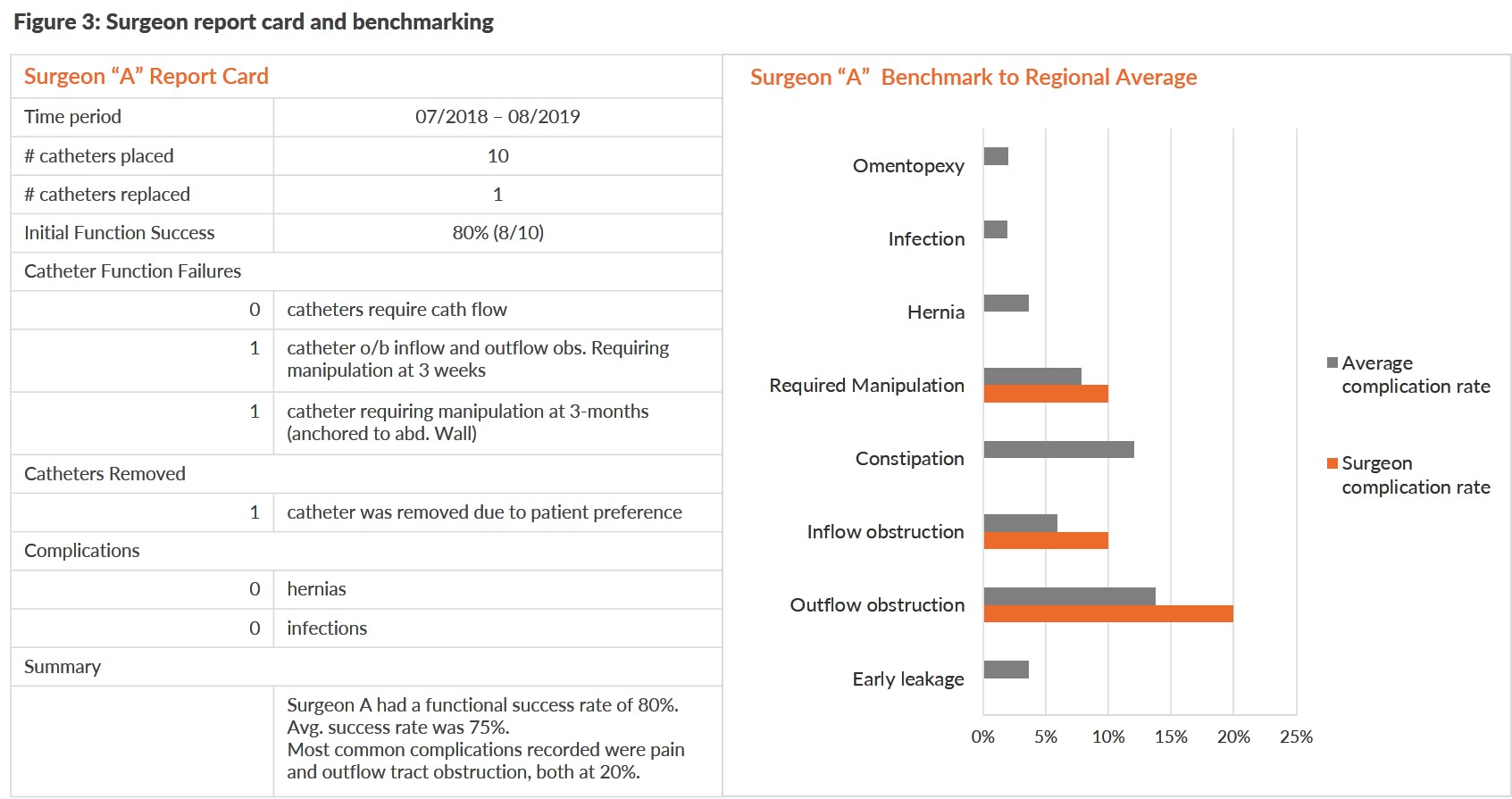

Step 2 – Review your data and create a report card

Next, you will need to determine how best to present this data back to the surgeons. My surgical colleagues have indicated that they do want feedback and want to know how they are performing in relation to their colleagues. We have recently created a report card for our surgeons. The report card is prepared for each surgeon and provides comparison of outcomes with that of their colleagues.

We try to update this report annually for each physician. While there is no published literature suggesting that report cards improve surgical outcomes for PD catheter insertion, we feel that this is an appropriate quality improvement approach whose impact will require further research.

Step 3 – Get together and present your case and data

Armed with this data, the next thing to do is to plan a meeting to engage your surgeons. This could be done individually or in a group. I have been conducting annual dinner meetings outside of the hospital setting with our surgeons for the last couple of years. I invited the surgeons, local nephrologists as well as nurses and other team members from our home dialysis unit. I personally feel that getting out of the healthcare environment lends itself to a more open conversation amongst our colleagues.

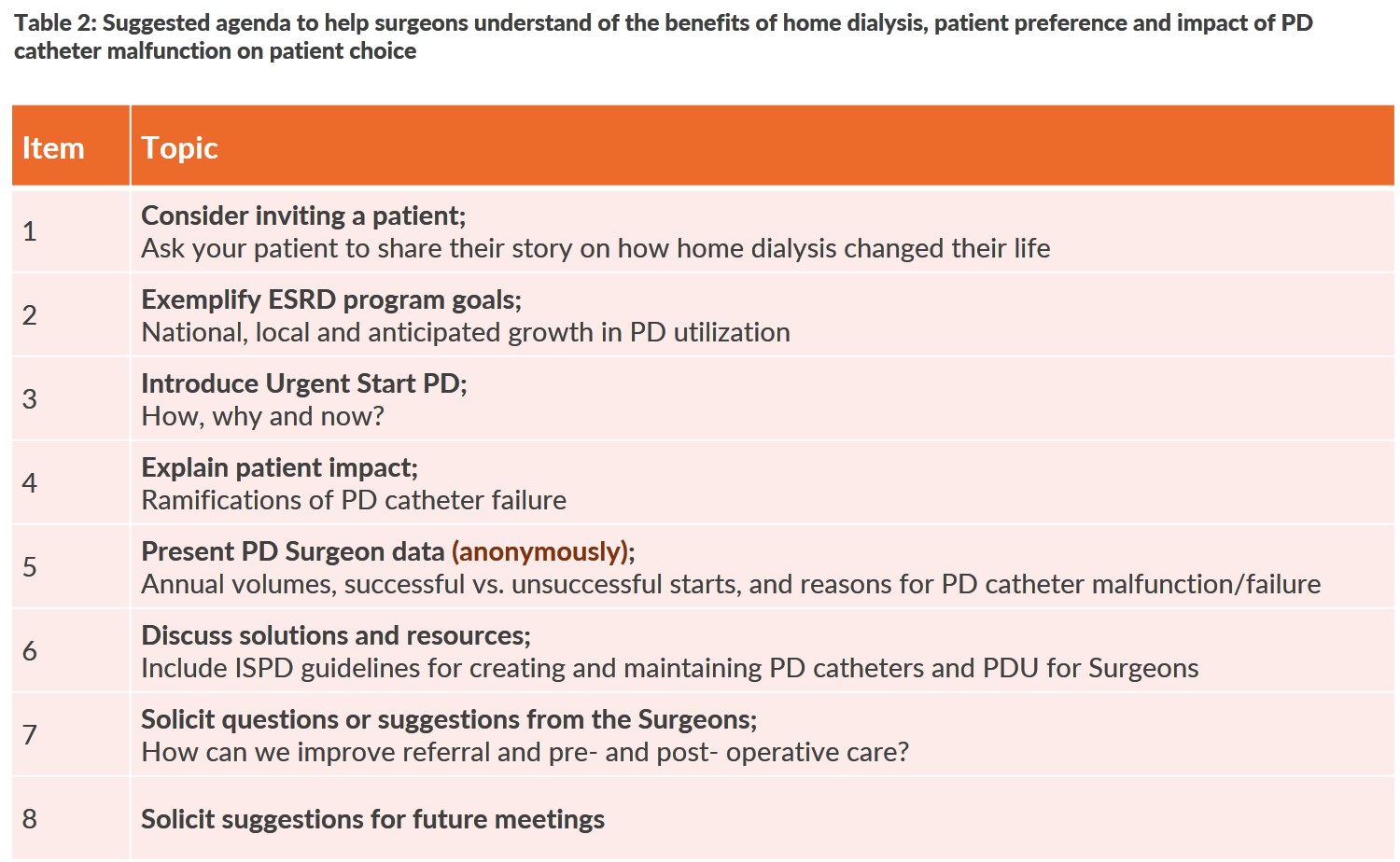

That being said, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way in which we interact and has also shown us that virtual meetings can also be very productive. Whether conducting an in-person or virtual meeting, we recommend being respectful of your colleagues’ time and having a succinct agenda. This agenda should help surgeons recognize the increased demand for PD, the need for long-term successful PD catheter placement and function, and how PD catheter malfunction can strip patients of this option as they undergo a life-changing therapy.

There are several talking points to help surgeons understand why they are being asked to do this procedure and the consequences of PD catheter failure. Surgeons may not be aware of the fact that many patients still “crash” into dialysis and most of these patients end up on in-center hemodialysis.7

They are not aware that with proper modality education, many patients will opt for home dialysis.8 They are likely not aware that about 90% of nephrologists and nephrology nurses would themselves choose home dialysis over in-center dialysis if kidney transplant were not an option.9 They may not be aware that data suggests patients on peritoneal dialysis generally have a survival advantage over the first few years compared to those on in-center hemodialysis.10 They are likely not aware that the annual Medicare costs for patients undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis was nearly $14,000 lower than for patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, yet fewer than 11% of prevalent dialysis patients were treated with this modality.11,12

Step 4 – Provide solutions

Providing feedback is not enough. We must be proactive in soliciting the advice of our surgeon colleagues as well as providing them with resources on best practices and ways to improve their PD catheter insertion skills. The ISPD has recently published guidelines which can serve as an excellent resource to help surgeons adapt their practices to achieve better outcomes.13

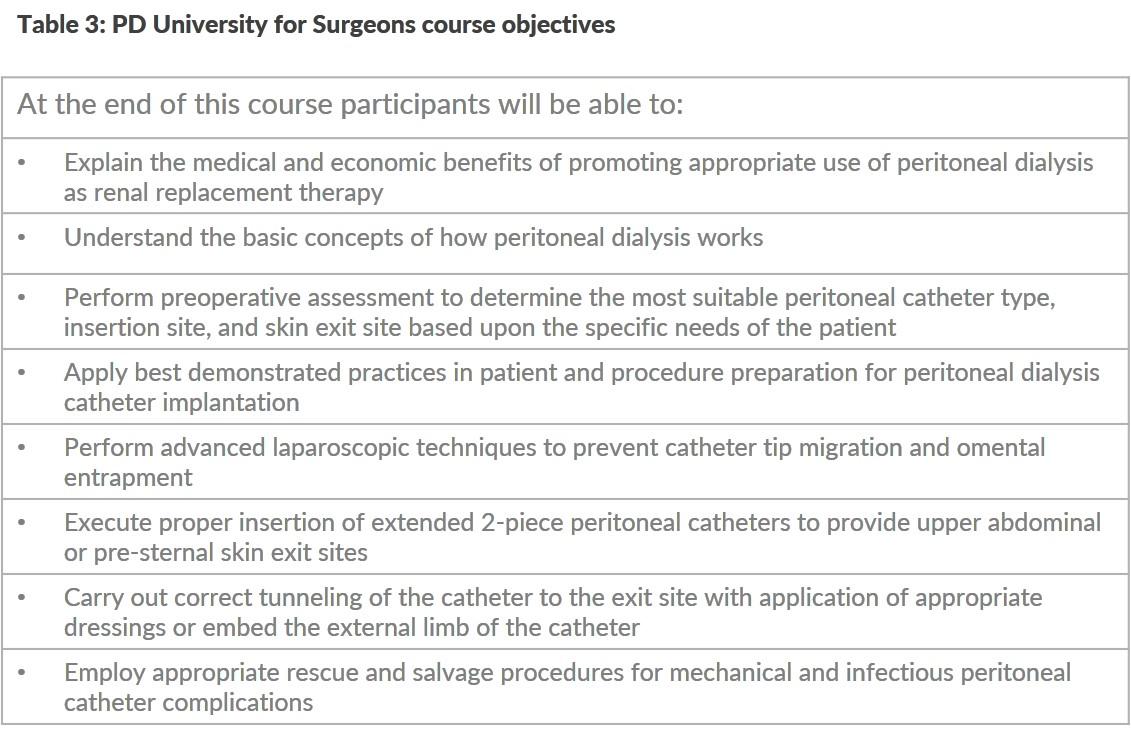

For surgeons who want a more interactive approach to skills improvement, consider recommending PD University for Surgeons.14 This 1-day course consists of didactic lectures followed by a hands-on experience in laparoscopic placement of PD catheters at surgical simulation stations.

Surgeons who completed this program found the course highly valuable and were much more confident placing PD catheters.14 A post-course survey found that there was significantly greater use of defined best practices compared to the prior practice.13

This program has also been adapted for the education of interventional radiologists and interventional nephrologists.15

Facilitating Better communication with Surgeons

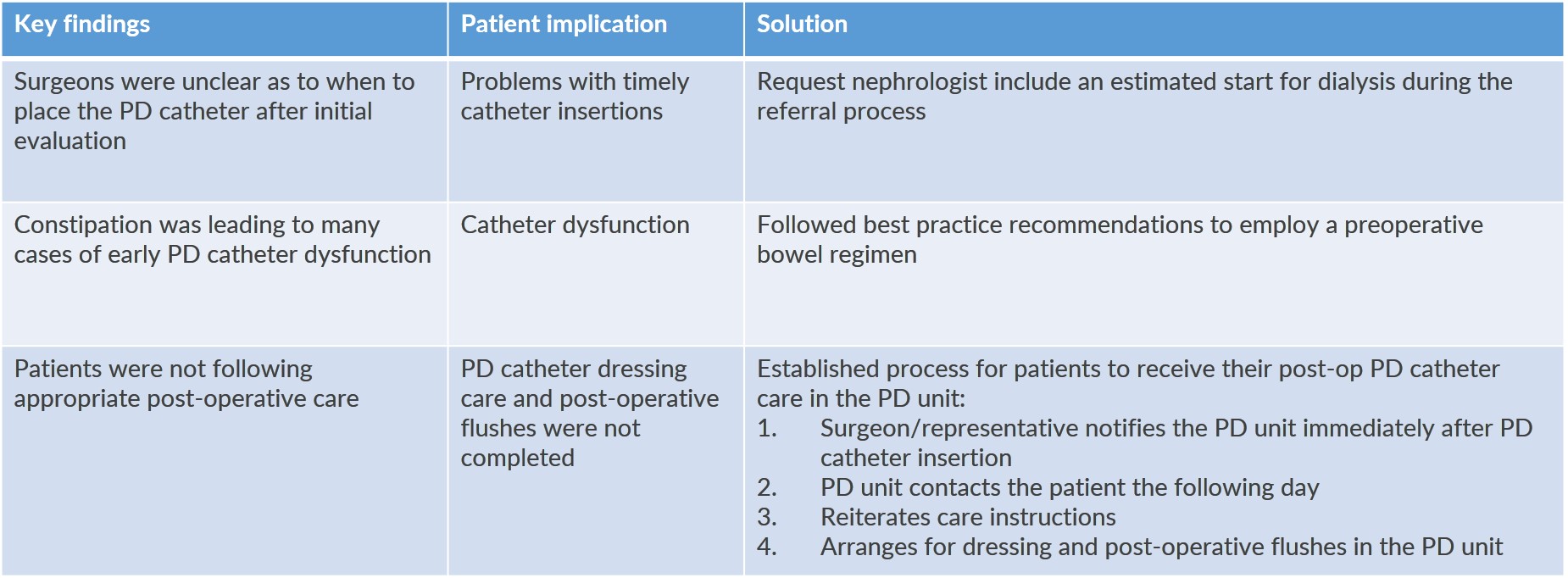

Following these steps has led to significant process improvement:

Meeting our Patients’ Needs and Fostering Patient Independence

In order to meet the preferences of our ESRD patients, and to provide them with the best options to lead a more independent life, the proper and timely placement of PD catheters is a must. Limited training opportunities for this procedure during surgical residency is a major barrier to achieving excellence.3 The above framework provides a platform to start communicating with our surgical colleagues and provide them with needed feedback to build on and improve their PD catheter insertion skills during and after residency training.

By engaging and educating our surgical colleagues they will come to understand how this seemingly small procedure can have a profoundly positive impact on the life of the patient as well as our increasing national healthcare costs.

Available Downloads

Risk and Responsibility

Not everyone will experience the reported benefits of home and more frequent dialysis. All forms of dialysis involve some risks. Peritoneal dialysis does involve some risks that may be related to the patient, center, or equipment. These include, but are not limited to, infectious complications. All forms of hemodialysis involve some risks. When vascular access is exposed to more frequent use, infection of the site, and other access related complications may also be potential risks.

Certain risks associated with home dialysis treatment are increased when performing independent dialysis because no one is present to help the patient respond to health emergencies.

Certain risks associated with home dialysis treatment are increased when performing nocturnal therapy due to the length of treatment time and because the patient and care partner are sleeping.