Peritoneal Dialysis in the Pandemic and Post-Pandemic World

Opinion article

International Practice Considerations After COVID-19

As England moves into the recovery phase from COVID-19, it is worth reflecting on newly enacted changes in clinical practice that should be sustained going forward. This could be particularly helpful to my colleagues in the United States, still in the midst of the pandemic.

In the United Kingdom, when we considered our response to the pandemic, there was heightened concern for those patients requiring dialysis or approaching the need for dialysis. National Health Service (NHS) England agreed with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that urgent guidelines should be written to support the response to COVID-19 and patients requiring or approaching the need for dialysis were an important first group to consider.

COVID-19 Dialysis Patient Care Guidelines

In-center hemodialysis (ICHD) remains the most common therapy for people needing dialysis in the UK. The latest UK Renal Registry report reported on 64,887 patient receiving renal replacement therapy. Of those, 55% had a functioning transplant, 37% received ICHD, 5% peritoneal dialysis (PD) and 2% home hemodialysis (HHD).1 Despite national guidance and improvement initiatives, the small rise in HHD was more than offset by a fall in PD numbers.

NICE guideline NG160 was published on 20th March 2020, at a time when understanding of the risk of COVID-19 was in its early stages.2 Prior to that work, the initial assessment of risk focused on the medical consequences of COVID-19. Patients with end stage renal failure were considered to be a high-risk group given the consequences of COVID-19, and the NICE guideline also assessed the risk of acquiring the infection in the context of hemodialysis treatments.

The rapid NICE guidance included a number of recommendations relevant to home dialysis. In particular, there was concern for a higher risk of ICHD patients acquiring COVID-19. Coupled with poorer outcomes in general, this could increase overall dialysis patient mortality rates. The high risk of COVID-19 acquisition reflected repeated attendance at facilities – the exposure risk of transport, waiting rooms, and the facility itself – were all areas of concern. Patients were encouraged not to miss sessions, asked to travel alone, not arrive early for an appointment, and call the facility on arrival before entering for a health check to minimize time spent in waiting areas.

The guidance however did make two significant recommendations about prevalent home dialysis activity and starting a home dialysis modality:

- 10.1 –> Continue and maintain current home dialysis provision (home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis) and maintain adequate supplies and staffing support.

- 10.2 –> Assess the resilience of care reliant on paid or unpaid carers, family and friends. Think about whether it is possible to increase home dialysis provision for new incident patients.

These two simple statements pointed to the central principle of minimizing exposure risk for the dialysis population by maintaining and extending the number of people on home dialysis therapy. Despite worries about staff sickness levels, it was important to maintain those programs during the crisis.

Much of COVID-19 has been of reporting anecdote. Case studies can be instructive, and one patient in our center emphasized how people’s priorities had changed. A 57-year-old man with progressive chronic kidney disease attended his low clearance appointment (virtually) and wanted to revise his decisions. He was being worked up for a renal transplant, but that program was suspended. He also required a full cardiac work up, which was also delayed due to COVID-19. Over many previous appointments, he had been clear that home dialysis was not for him. The pandemic changed that view. With an expected date of dialysis initiation a few months away, he weighed the risks and felt peritoneal dialysis was now the way forward.

That is one anecdote amongst many across the UK; PD starts have been significantly increased during the last two months. What changed and what is needed to sustain that switch?

Characteristics of centers that have successful Peritoneal dialysis programs

Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered limited change, there is nothing fundamentally different before this pandemic and now.

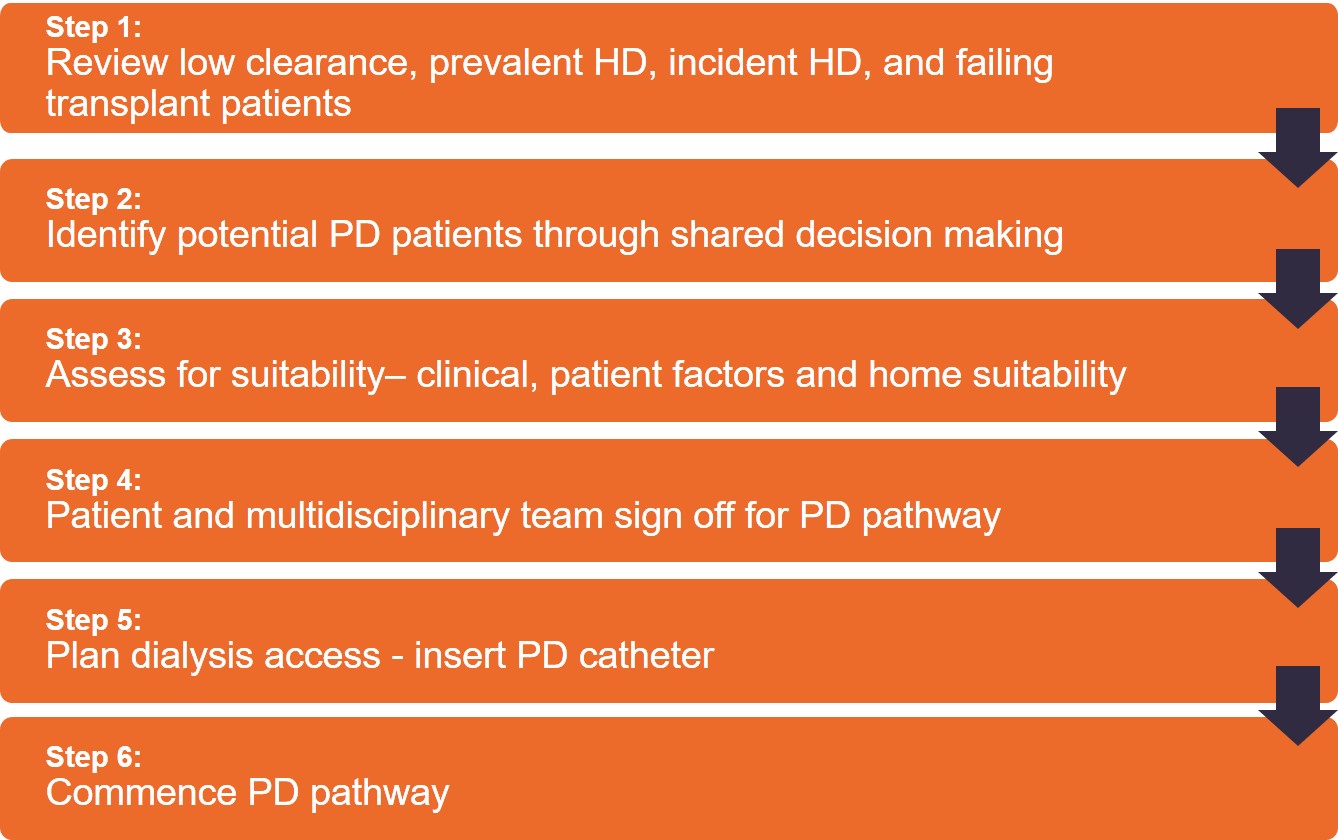

What elements make up the infrastructure or mechanics of a program? It should consider how people are selected for a PD program, how patients start PD, how they are maintained on the therapy and importantly, how dropout is managed. For example, Figure 1 adapted from Blake et al, considers the process of selection and initiation onto therapy.3

In terms of recruitment, the first step is to consider all potential candidates. That is not just restricted to the pre-dialysis population but those on in-center hemodialysis and those with a failing kidney transplant. One marker of successful programs is that the leadership culture of home dialysis, and PD in particular, are shared across the service as a whole. Individuals with end stage renal failure, of a necessity, will likely experience more than one modality of therapy. Thus, any healthcare professional who touches on that pathway of care needs to be able to transition a patient to the right choice, and avoid working within silos.

Prescribing High-quality, goal-directed Peritoneal Dialysis

Shared decision making (SDM) is an important concept to adopt and is endorsed by the ISPD as part of goal directed therapy. The aims of these care goals are:4

- to allow the person doing PD to achieve his/her own life goals

- to promote the provision of high-quality dialysis care by the dialysis team

Implicit in that statement is that an individual’s life goals have equal or more weight in the delivery of care. The concept is simple but the successful delivery of SDM is challenging.

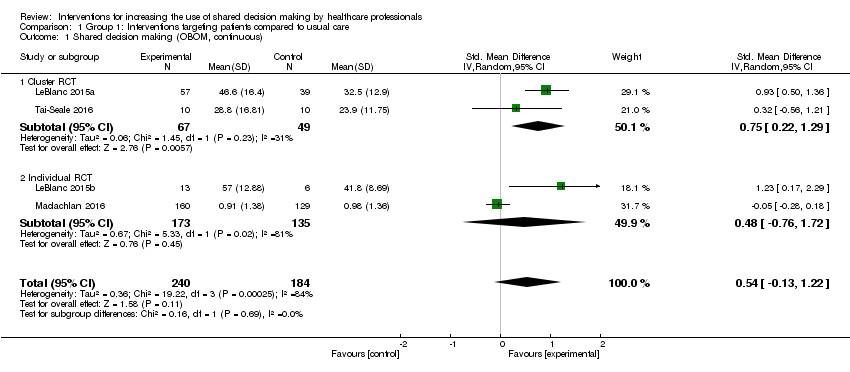

A variety of tools and training packages have been devised targeted at both professionals and patients, and the evidence for that is limited.5 In doing so, it is useful to reconsider the binary decision-making processes that were the norm in decision making.

Challenging binary decision-making

For a patient to successfully start PD, all of the steps in this process need to be successful so the effectiveness of the process as a whole can be dominated by the weakest component. This leads to a well-constructed training program. Most critically and important, is that the placement of a PD catheter is effective, safe, and timed correctly.

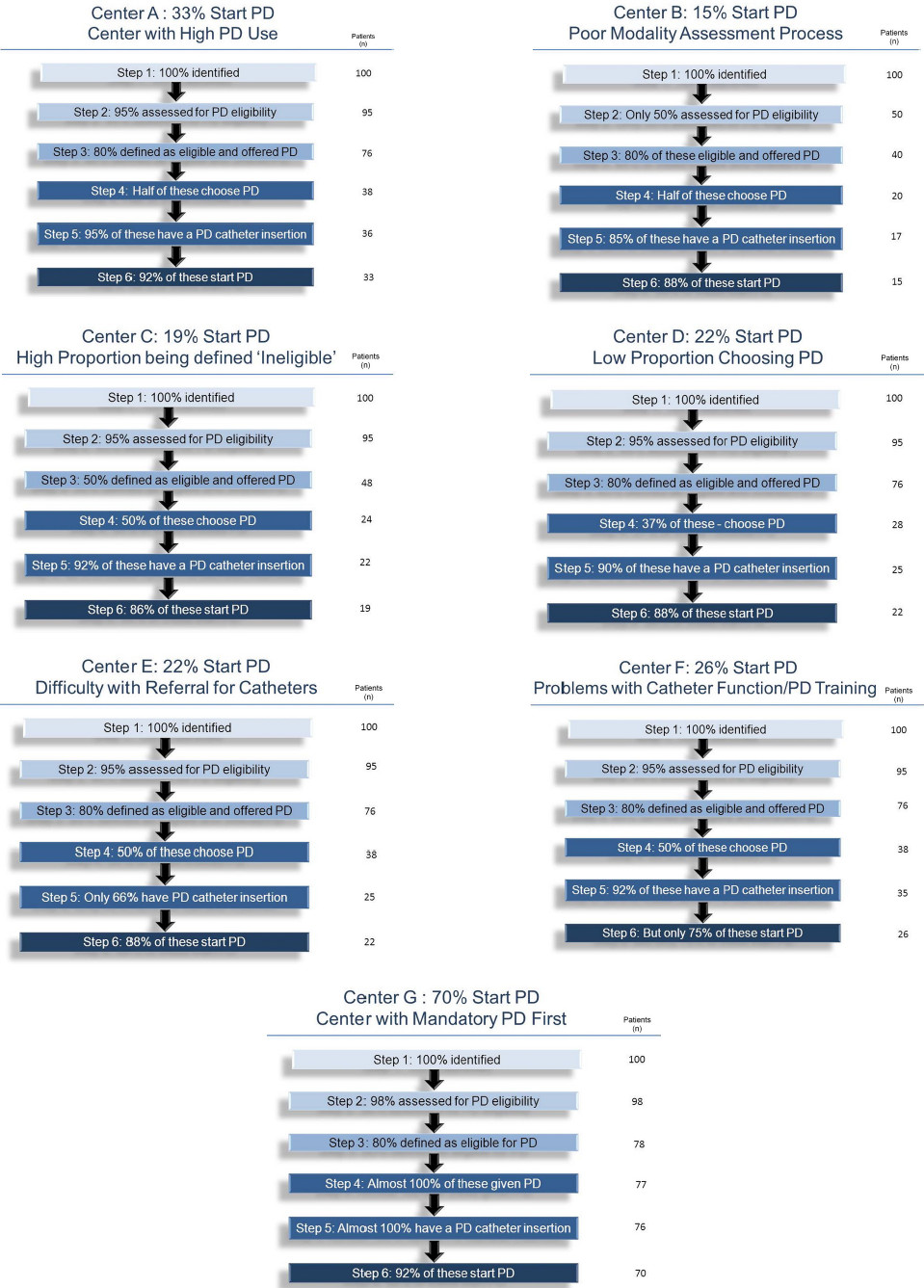

Blake et al., compared pathways to PD in 7 theoretical centers showing how 100 patients could progress through the 6 step model:3

In theory, the best case scenario shows 70% of patients starting PD.

In practice, even if each step is 90% effective, only 50% of patients who wished to do PD, actually did so.6

Steps 3 and 4 are essential to evaluate the suitability of both individuals and the environment to undertake a home therapy, but a key point should be made. It implies a sign-off. A more nuanced view would be that it is the role of the clinical team to prove that a willing individual cannot undertake a home dialysis therapy. This is in contrast to the situation where an individual has to prove to the satisfaction of the clinical team that they are ‘safe’ to go home. In other words, the clinical team should solve or remove problems, rather than create barriers.

Like buying a car, there is often no one right answer. What has become clear is that clinicians may focus on mortality risk to support their bias. In doing so, they will often censor patient choice. Yet, if clinicians are asked about personal preferences or views, it is often recognized that home therapies offer improved quality of life.7 On the patient side, the SONG PD work stream confirmed that while patients valued improved medical outcomes (reduced mortality, fewer infections and cardiovascular events), life participation was just as important.8

Overall, the objective should be to deliver a therapy that is safe and targeted to those agreed goals but also recognizes the need to move on when appropriate. The components of a successful PD program are relatively simple; recruit more people to the program than are leaving, accepting that leaving, in itself, is not failure. And, a transplant, or a well managed transfer to hemodialysis or careful end of life care, is an important part of a goal directed approach.

PD in the Post-pandemic World

Moving out of this pandemic, there is an opportunity to reset the approach to peritoneal dialysis. The elements are known and can enable us to deliver successful care to people with end stage kidney failure. Putting the opportunity and elements together requires a quality improvement mindset, to ultimately deliver both large and small nudges to move the needle towards greater home dialysis utilization.

Measures against clinical and patient outcomes, include balancing measures for those unintended consequences. Use those measures to improve the system rather than to judge.

There are no new solutions to increasing the utilization of PD. Rather, as the Blake model describes, it is a matter of small incremental gains. The challenges for the service that I work in has been to provide leadership (including patient champions), provide a permissive culture across the service, develop the clinical pathways (including PD access), and measure to improve.

It takes time, but it is sustainable.

Potential Risks

Not everyone will experience the reported benefits of home and more frequent dialysis. All forms of dialysis involve some risks. Peritoneal dialysis does involve some risks that may be related to the patient, center, or equipment. These include, but are not limited to, infectious complications.

Certain risks associated with home dialysis treatment are increased when performing independent dialysis because no one is present to help the patient respond to health emergencies.

Certain risks associated with home dialysis treatment are increased when performing nocturnal therapy due to the length of treatment time and because the patient and care partner are sleeping.