Peritoneal Dialysis in the Pandemic and Post-Pandemic World

Opinion article

International Practice Considerations After COVID-19

As England moves into the recovery phase from COVID-19, it is worth reflecting on newly enacted changes in clinical practice that should be sustained going forward. This could be particularly helpful to my colleagues in the United States, still in the midst of the pandemic.

In the United Kingdom, when we considered our response to the pandemic, there was heightened concern for those patients requiring dialysis or approaching the need for dialysis.

Learn MorePeritoneal Dialysis in the United States Amidst COVID-19

Opinion article

Clinical Practice Learnings with Potential Post-Pandemic Application

The world is amidst a public health crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 will remain a primary healthcare concern until a vaccine and effective medications are discovered, which may take many more months.1 End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) patients are at particularly high risk of this coronavirus infection because of chronic immunocompromised state, a high burden of co-morbid conditions, and high healthcare utilization.

Learn MoreDecreasing Non-COVID-19 Hospitalizations in Dialysis Patients

Opinion article

Physician and Physician Extender Clinical Practice Considerations

Caring for Dialysis Patients During the COVID-19 Epidemic

On March 13, 2020, the U.S. administration instituted a national emergency, as nearly 200,000 COVID-19 cases presented worldwide.1 This is a novel disease and a rapidly evolving situation in the U.S., with the number of newly confirmed cases increasing by 20k-30k per day.2

The COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to strain many hospital systems and supply chains, putting hospital beds, tests, masks, gloves, and antibacterial and pharmaceutical supplies at risk.

Learn MoreTransitioning from Peritoneal Dialysis to Hemodialysis

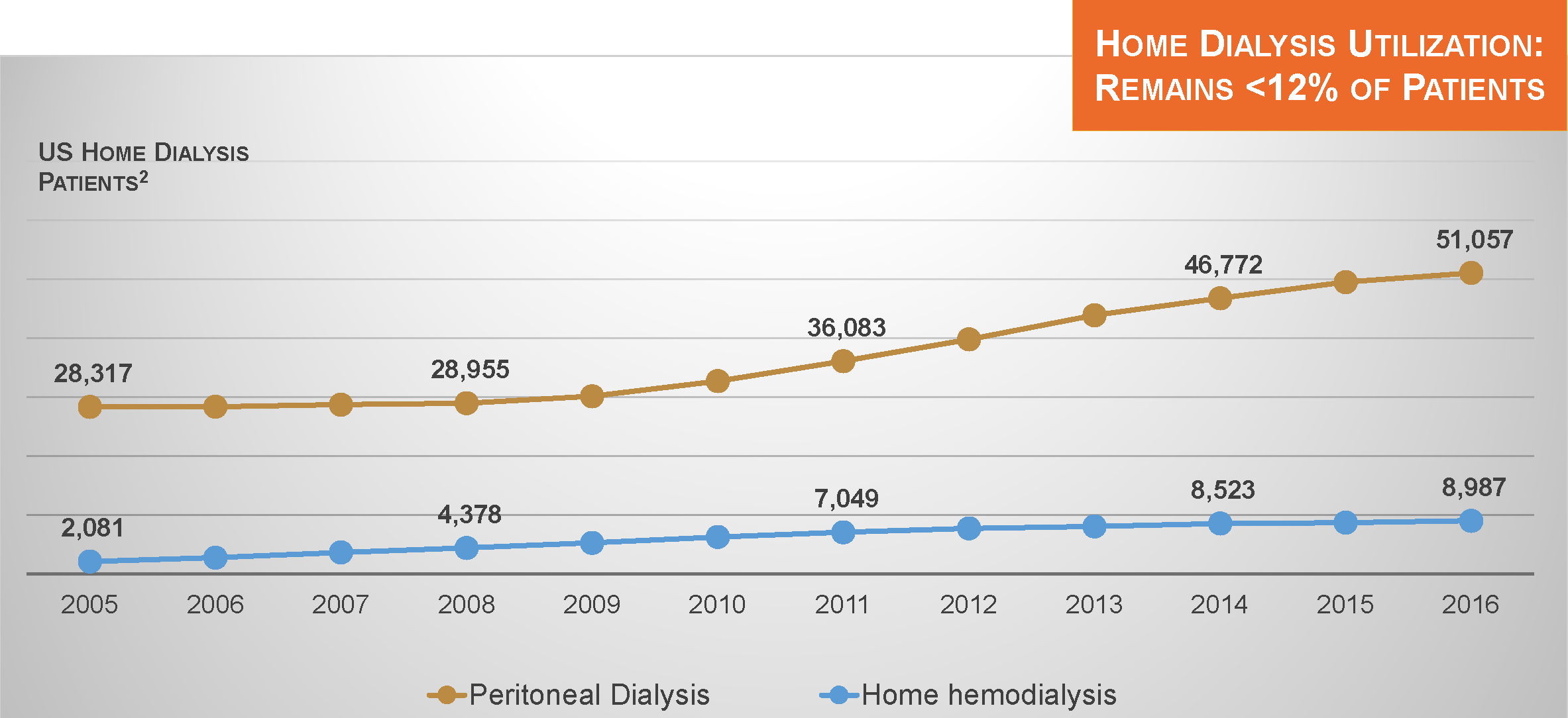

During the past decade, the use of peritoneal dialysis (PD) in the United States has grown substantially.1

In 2009, 7.5% of dialysis patients were treated with PD; by 2016, the statistic had increased to 10.0%.1 And according to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), 10.5% of dialysis patients with new Medical Evidence Report (“2728”) submissions in 2017 were treated with PD.2 In addressing the goal of dialyzing more patients at home, this is a genuine accomplishment.

Learn MoreRecasting Kidney Failure as Cardiovascular Disease

Total Medicare expenditures on the health care of patients with permanent kidney failure have steadily risen to more than $35 billion per year, although per capita expenditures on the care of dialysis patients have been relatively stable in recent years.1 This conflict in trends can be readily explained by the seemingly unstoppable increase in the number of people undergoing chronic dialysis.

Dialysis Patient Population Growth

Today, that number exceeds 510,000. Nevertheless, the annualized rate of growth in the dialysis patient population has recently slipped below 2%.

Learn MoreWhen is More Frequent Hemodialysis Beneficial?

In 2017, Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) began to promulgate draft local coverage determinations that include restrictive language regarding Medicare reimbursement for additional hemodialysis sessions. An important element of the draft determinations is medical justification, or the clinical conditions that constitute evidence-based rationale for the prescription of more frequent hemodialysis.

Suri and Kliger, who were both investigators in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) trial, posed and answered this timely question in a thoughtful narrative review that appears in the July/August issue of Seminars in Dialysis.

Learn MoreCardiac Arrhythmia: An Ominous Side Effect of Thrice-weekly Hemodialysis?

Many studies represent incremental gains in our understanding of human pathophysiology. Some studies, especially large randomized clinical trials, can singlehandedly change the standard of care. Other studies, at the most unexpected times, flash a signal that raises the question of whether the widely accepted standard of care is simply inadequate.

In the April 2018 issue of Kidney International, Prabir Roy-Chaudhury and colleagues published one such study. These investigators reported data from a prospective, multicenter study, the Monitoring in Dialysis (MiD) Study, which was conducted in both the United States and India and aimed to estimate the proportion of thrice-weekly hemodialysis patients who experienced clinically significant arrhythmias during 6 months of follow-up.

Learn MoreHypertension in Dialysis Patients

The link between hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, and sudden death is clear. In the dialysis population, persistent hypertension is observed in the majority of patients, making it a fundamental and unmet challenge. Accumulating evidence shows that ambulatory blood pressure is a better predictor of survival than in-unit blood pressure—and, importantly, that ambulatory blood pressure is linearly associated with risk of cardiovascular events.1,2

As clinicians, how should we respond to this challenge?

Learn MoreInternational Guidelines for Increased Hemodialysis Time and Frequency

During the past 10 years, there has been a proliferation of research about intensive hemodialysis, including both longer and more frequent hemodialysis sessions. The accumulation of data from studies has led to the development of clinical practice guidelines about hemodialysis time and frequency, with a focus on identifying indications for increasing time and frequency.

In the United States, Medicare requires medical justification for reimbursement of additional hemodialysis sessions (i.e., treatment beyond 3 sessions per week). Clinical practice guidelines not only from the United States, but also from Japan, the United Kingdom, Europe, and Canada together encourage physicians to consider applications of longer and more frequent hemodialysis sessions in patients with cardiovascular complications, including left ventricular hypertrophy and uncontrolled hypertension; hemodynamic instability during dialysis, possibly due to excessive ultrafiltration intensity; hyperphosphatemia; and malnutrition.

Learn More